I’ve started writing fifty-year memory essays of late. It’s probably because I am now far enough past fifty to recall the world I lived in fifty years ago. I mean, I have written about The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and Double Indemnity (1944) as well, but if I have to go back one hundred or seventy-five years for nostalgia pieces – well, I can’t really bring as much of myself to them. So I’m looking at you, 1969.

Trouble is, 1969 wasn’t much of year – at least not in terms of American film. Of course there were exceptions. There are always exceptions. But those seemingly revolutionary movies – Oscar-winner Midnight Cowboy, Easy Rider, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice — they all feel very dated to me. You might point to more revolutionary titles like The Wild Bunch or Medium Cool, and I’m sure you each have your own favorites. But when I look back, it strikes me that the American film industry was awfully tepid despite being smack dab in the middle of a cultural revolution.

Fortunately, the rest of the cinematic world was not so meek. African film took a giant step forward with the founding of FESPACO, a festival of African cinema in Burkino Faso. Cahiers du Cinema published Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni’s clarion call for a new politically engaged form of criticism, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism.” Meanwhile, Jacques Rivette was signaling an evolution in the Nouvelle Vague with his titanic L’Amour fou. All across Europe – from the British Isles where Ken Loach was making us cry with the story of a tough kid and his falcon, to the USSR, where Andrei Tarkovsky was making us gasp in awe at the story of a man and a giant bell – there were new and exciting things happening on movie screens.

Kes and Andrei Rublev are pretty well known to film fans. Here are five international movies from 1969 that I think deserve a little more attention. In no particular order, other than alphabetical…

The Color of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov, USSR)

Parajanov studied film under some of the giants of Soviet cinema – Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Savchenko – and early in his career, he proved quite capable of making standard-issue narratives that would entertain the public. Then he saw the above-mentioned Tarkovsky’s first movie, Ivan’s Childhood, and he immediately disowned the movies he had made up to that point. From the early 1960s, Parajanov embarked on a tortured quest to invent a new film language, one that used imagery and color and sound in place of traditional narrative. His remarkable eye crafted Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors in 1965. Despite international acclaim, it was deemed too strange by Soviet authorities. Thus began the rest of Parajanov’s life – always poor, often imprisoned, rarely able to work. But he did create his masterpiece, originally titled Sayat-Nova, in 1969 (though trouble with officials would hold up its international release.) It is a biographical portrait of the 18th century Armenian troubadour Sayat-Nova, but it dispensed with traditional narrative, and instead focused on the internal inspiration. Parajanov’s flat frames recall older religious iconography and his use of color and music washes over any viewer who allows it in. This may harken back to Jean Cocteau’s Blood of the Poet and may predict later works of Derek Jarman, but Parajanov was like no other before or since. He was rarely able to build on The Color of Pomegranates, and that is a loss to the world of movies. But we do have this film to remind of us all of the areas cinema may still explore.

The Cow (Dariush Mehrjui, Iran)

Both Dariush Mehrjui and Masoud Kimiai released their second feature films in 1969, and with them, they launched the Iranian New Wave, and helped create one of the most innovative film communities in the world over the ensuing fifty years. Kimiai’s Qeysar is quite good. Mehrjui’s The Cow is astonishing. It tells the story of a small Iranian village where one gruff man – (an electric performance by Ezzatollah Entezmai) – forms an unhealthy attachment to his beloved cow. Such is the nature of his adoration that his neighbors fear how he will react when the cow dies. They devise a story to feed him – the cow has run off. Entezami’s subsequent breakdown is the stuff of movie legends – a mesmerizing final sequence that needs to be seen to be believed. Mehrjui’s unadorned treatment of his villagers – they are neither idealized nor villainized – stood in stark contrast to what audiences had seen before. In this, he was no doubt influenced by Italian neo-realism. But there was a quality unique to Iran in The Cow. A blend of pragmatism and cruelty and compassion, all tinged with a strong measure of absurd madness. Mehrjui, who had earned his B.A. in philosophy from UCLA, brought a Western mentality to his material. Perhaps that helped The Cow garner awards from European festivals. Indeed, though initially banned by the very state apparatus that funded it because it did not present a modern, happy vision of rural Iran, all bans were lifted after Mehrjui was recognized at the Venice Film Festival in 1969. That tenuous relationship filmmakers have had with their own government in Iran has persisted for the past fifty years.

Cremator (Juraj Herz, Czechoslovakia)

Herz came along during a heady time for Czechoslovakian cinema. He served as an assistant to both Brynych and Kadar, and acted for his friend and fellow puppeteer Jan Svankmajer before embarking on his own directorial career. Cremator, his third film, is a terrifying fairy tale about the mundane nature of evil. Based on a novel by Ladislav Fuks, it tells the story of Karel Kopfrkingl, a portly self-styled humanitarian, who runs a crematorium because he sees cremation as the most benevolent way of freeing the human soul from its earthly bondage. Kopfrkingl’s already-misguided thoughts on the subject get an adrenaline rush when the Nazis seize power in Czechoslovakia and the entire field of cremation takes on new and horrifying meaning. Blanketed by non-stop narration from Rudolf Hrusinsky as the unctuous, song-songy Kopfrkingl, Cremator becomes a hypnotic journey into the madness of the Holocaust. DP Stanislav Milota combines deep focus with wide-angle lenses to add to the disorienting hallucinatory feeling. Herz had spent time in Ravensbruck during the war, and though we never glimpse a concentration camp in Cremator, it nonetheless stands as one of the most casually terrifying depictions of Nazi horror ever captured on film.

Double Suicide (Masahiro Shinoda, Japan)

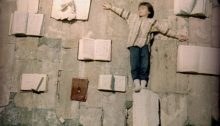

Shochiku was one of the grand old studios of Japanese film, but it also helped usher in the ‘new wave” in Japan in the late 1950s. Oshima and Yoshida led the charge, but Masahiro Shinoda may have been the most revolutionary. He came from a theatrical background, and his best movies always have a theatrical flair about them. Nowhere is this more evident than in Double Suicide, which manages to be both the most traditional and most revolutionary of the Shochiku output of the 1960s. It is drawn from a bunraku (a style of puppet theater) by the writer Chikamatsu. The story had been filmed before by no less than Japanese master Kenji Mizoguchi, but Shinoda brought an eye both traditional and modern to the material. The story is classic melodrama. A husband and father has fallen hopelessly in love with a courtesan, and she returns his affection. But their duty to their family and society crashes headlong into this passion and we know from the outset that tragedy is the only possible resolution. Shinoda begins his film as a virtual documentary on the art of bunraku. We see the puppets being prepared. We hear the director discuss the script for the upcoming film. We see the puppet masters, dressed in all black, prepare themselves for performance. Then, seamlessly, the action is taken over by live actors who replace the puppets. But the puppeteers remain always in the background, always dressed in black. Occasionally they step forward into the action at key moments. They become a surrogate audience, wanting to exert some control over the unfolding tragedy, but ultimately incapable of doing so. The effect is astonishing, blending reality and theatricality until all lines blur. Shinoda cast his own wife Shima Iwashita in the dual role of courtesan and wife, further erasing lines of demarcation between what is real and what is imagined. It may have presaged Luis Bunuel’s use of two different actresses to play the same character eight years later in That Obscure Object of Desire.

The Price of Power (Tonino Valerii, Italy)

President James Garfield was assassinated while speaking with his Secretary of State at a railroad station in Washington, DC. The gunman, Charles Guiteau, shot the president twice, and was quickly apprehended. The wounds should not have been fatal, but infection set in, and Garfield died eleven weeks later. So why, in The Price of Power, does President Garfield die as the result of multiple gunshots coming from unseen gunmen while riding in a carriage next to his wife in Dallas, Texas? Why does he die that same day? Why does his wife refuse to change out of her blood-spattered finery after the shooting? And why is an innocent man deemed by authorities to be the lone gunman in the assassination? It’s because the filmmakers involved in The Price of Power were not making a moving about James Garfield. They were making one about John Kennedy – the first major consideration of the Kennedy assassination in a dramatic film. Up to this point, the Kennedy assassination was strictly off-limits, deemed to painful for consumption by the American public. It had derailed the release of John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, and it had caused panic amongst the producers of the soon-to-be-released Charade when they realized a character even uttered the word “assassinated.” But, not surprisingly in hindsight, it took an Italian western to first confront the national horror. By 1969, the Italian western (sometime pejoratively referred to “spaghetti western”) was a well-established and profitable international genre. Its stylistic flourishes were helping rekindle the mostly moribund American Western in movies like 1969’s The Wild Bunch. And the lord master of Italian Westerns, Sergio Leone, made arguably his greatest movie that same year – Once Upon a Time in the West. There has been much speculation about how much Valerii, who had served as an assistant to Leone, was guided by the great man’s hand in directing The Price of Power. It hardly matters. The Price of Power is not nearly as stylistically innovative as some of Leone’s or Corbucci’s best films, though it is very well made, with a number of strong set pieces and excellent performances. I include it here not because of any revolutionary style, but because of revolutionary substance. As American film began to soar again in the early 1970s, filmmakers would begin to examine the Kennedy assassination. But it took a foreign movie to open that door.

So there you have it. Five films spanning the globe in 1969. Different styles. Different genres. Revolutionary in their own unique ways. All worth remembering for their inherent cinematic power, as well as for the way they helped steer the course of film history over the past fifty years.

Comments

4 responses to “The Cinema of 1969: Five classics you may have missed”

Happy New Years, James.

Thanks Pete. Check out The Painted Bird when you get the chance.

Thanks for this list, Jon. I have seen ‘Pomegranates’ and ‘The Cremator’, both at the NFT in London, in my teens. (A long time ago!)

I will certainly look out for your other suggestions.

Best wishes, Pete.

I’ve not seen most of these, Jon. Will have to seek them out!