Thoughts from a cinematic memoir written on Earth by Philippe Mora.

In Los Angeles in 1979 I was making a film about the Sixties called The Times They Are A-Changin’ for Columbia and Casablanca, greenlit by Daniel Melnick, producer of All That Jazz. Because of some controversial content my film was eventually stopped before release by an incoming regime. This content included the Zapruder film which I had received permission to use from Zapruder’s son, a lawyer in Washington, D.C. On my behalf Eric Clapton had also received permission to use the Bob Dylan song referenced in the title. NASA would also cooperate with Apollo moon footage. I had iconic elements ready to go. The stopping of that film is another story. This article is about the moon, the first landing being the prologue and epilogue of my film.

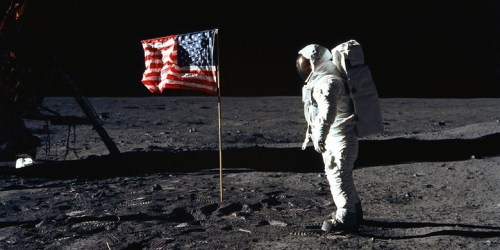

Buzz Aldrin near the lunar module during Apollo 11 mission (NASA file photo)

Researching for the film in 1979 I was walking down the Avenue of the Stars in Century City, Los Angeles with Dr Thomas O. Paine, 58, on the way to Hamburger Hamlet for lunch. He was the Administrator of NASA when man landed on the moon. You could accurately say he put us on the moon. He was extraordinarily humble, wise and saddled with the rare charisma of the few who are markers in human history. We ate hamburgers and French fries.

His New York Times obituary stated: “Dr. Paine joined NASA as its deputy administrator in January 1968, then served as its administrator from March 1969 to September 1970. During his years with the administration the first seven Apollo missions were launched, some 20 astronauts orbited the earth, 14 flew to the moon and four men walked on the lunar surface.”

When I met him he was sitting, Yoda-like, behind a big desk as President of Northrop. One of the “greatest generation,” he was a tough, brilliant fellow and had served in submarines in WW2.

Thomas O. Paine and Nixon wait for Apolo 11 astronauts

As we walked he asked me about my background and I told him about my father being German Jewish and a member of the French Resistance. He said: “Then you have good survival genes.” This was slightly off putting but I put it down to him being a scientist. Over lunch he chuckled at my mention of Georges Melies’ Trip to the Moon being one of the first fiction films made.

He was friendly with the Bottoms family of actors in Santa Barbara and that was our connection. He had a pretty good knowledge of film. He liked Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey, but having been in charge of the real thing he sort of dismissed it as lightweight, but with a smile, respect and courtesy. He laughed in the affirmative when I asked him if the renowned aerospace engineer Werner Von Braun was like Dr. Strangelove. This triggered his telling of a long story, which I summarize here.

“We called the German group at NASA the Duelling Scars because many of them had fencing scars as signs of class. Von Braun obviously was a great rocket scientist, but he was even more helpful to me when I needed money for the program. In his, yes, Strangelove accent he explained that when he needed money for the Nazi rocket program he would invite Hitler to see a big rocket launch. This display always immensely impressed Hitler and he would immediately ask: ‘How much more do you need?’ So I suggest you invite President Johnson down here and I will arrange for a big rocket launch. So I did that and I was sitting next to the President and Von Braun. The rocket launched and it was spectacular and loud. The President turned to me and said: ‘How much more do you need?’ Von Braun later congratulated me with a smile and no comment.”

Later in the NASA film archives, then in a rather ramshackle building, I watched 16MM sound films of Von Braun explaining to President Kennedy how the Saturn Five rocket would work, demonstrating with a model. You could see JFK was riveted. In the same archive I came across the fact that NASA had shot much in high-speed 70MM film of every launch for scientific purposes. NASA must have been the biggest consumer of film in history at that time with multi cameras on every event.

A scene from Georges Méliès’s 1902 film A Trip to the Moon

ELEVEN YEARS EARLIER

I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey when it opened in London at the MGM cinema in Soho in 70MM anamorphic six track stereo in 1968. SPECTACULAR! But the year 2001? That seemed such a long way off. I had loved How The West Was Won and I had read that originally 2001 was called How The Solar System Was Won. I’d heard that Kubrick had gotten MGM to commit to his space epic by pitching it as How The West Was Won in SPACE. That made sense.

By the time Arthur C Clarke and Kubrick started making 2001 a generation had smoked quite a bit of pot. In 1968, 2001 folded perfectly into that zeitgeist either by accident or design. Smoking a joint and settling into a slow Space Odyssey for a generation eventually turned the film into a financial success, and then a game changing film in cinema history. As a young artist in London at that time, Francis Bacon and Stanley Kubrick became my heroes.

We were all reading the U.K Flying Saucer Review before 2001 was released, so we were all primed (on the Kings Road, Chelsea, at least) to jump into the possibility of aliens. Apparently even Prince Philip read the FSR. Flying saucers as a subject were both hip, smart, crackpot and staid. Kubrick and Clarke, sort of strange puritans with a dry sense of humor, didn’t reference FSR stories like that of Villa Boas in Brazil, who was raped by a green woman alien and famously survived with a radioactive penis. That would have been quite a scene in 70MM.

A scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

Anyway, we all enjoyed 2001 a few times, usually followed by a Chinese meal, which was very close to the cinema. We braced for the real thing next year in 1969. The Apollo program was full on and we were going to actually land on the moon. We even bought a TV set in anticipation of the landing, quite an expense for us. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King had been killed. The Vietnam War was in full swing with napalm horrors escalating. Andy Warhol had even been shot by Valerie Solanas, head of SCUM or the Society for Cutting Up Men. He survived but with all this going on our psyches were in danger. If humans could land on the moon it would somehow make all the dreadful calamities on Earth fade at least temporarily.

Incredibly we successfully, precisely landed on the moon. No black monoliths were to be found, but it did show we humans could do more than kill each other and that was mass therapy.

BACK TO 1979

I had all this in my mind when I had lunch with Tom Paine. I asked him about the Vietnam War protests and how that all figured into his mind at the time. He said it deeply bothered him and on the day of the Apollo 11 launch there were protestors outside a NASA gate. He decided to personally go and talk to them and explain what was happening and why he thought it was important for humanity and science. Sadly we have no record of his talk with the protestors but it did calm things down. As a practical aside, he said he told them getting to the moon was not the real problem. His concern was getting the three astronauts back safely to Earth. He said you can start a car many times by turning the key, but one day it does not start. His nightmare was that the two astronauts could be stuck on the moon, their death televised live.

Wernher von Braun’s Dr. Strangelove look

So as we come now to the end of the Fiftieth Anniversary of that lunar landing I can’t help referring again to the two key films that resonate with the event, its history and its date; Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick was a master pre-digital film maker but he was also in tune with his times, and his success reflected that tune. It’s one of the mind confounding ironies that without a Nazi scientist, Dr Werner Von Braun (or Dr. Strangelove), we never would have gotten to the moon in 1969. And for anyone who saw Kubrick’s space film prior to 1969 it prepared the mind for the experience of humans in space in a deep way. In an interview with a Japanese film buff, Kubrick was forthcoming about the enigmatic ending. He said it was simply aliens putting the human in an alien version of a zoo so they could observe him. The oddness of the decor was wrong in much the same way as the environments we create for animals in our zoos.

Before my lunch was finished Tom Paine told me briefly about his plans to build a base on the moon and look towards Mars. Unfortunately President Nixon, became in charge and was more interested in hounding his earthbound “enemies” and began curtailing the Space Program or we would already be eating McDonalds on the Moon.

Comments

3 responses to “Meeting the man and movies that put us on the moon”

A terrific article, Phillipe! Very enjoyable!

That’s a great article, Philippe. And I say that as someone who has zero interest in space travel. 🙂

Best wishes, Pete.

Wonderful piece, Philippe!