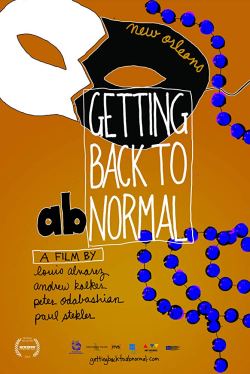

Veteran documentary filmmaker and Hollywood professional Peter Odabashian is so laid-back and gregarious that you may, while speaking to him, forget that he works in one of the most grueling of industries … one that is informed by strenuous workloads, stiff competition and potentially small financial rewards—if any are reaped at all. Despite these challenges, however, Odabashian has cultivated a portfolio of intelligent, sensitive pictures that have transcended the frameworks of the genre, ranging from Getting Back to Abnormal (2013), an account of the societal developments in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina that he co-directed and co-produced with Louis Alvarez, Andy Kolker and Paul Stekler, as well as edited, to his latest directorial effort, Somewhere to Be (2018), which takes a unique look at a New York City senior center. In this interview, CURNBLOG examines Odabashian’s oeuvre, techniques and perspectives on individualism and creativity in the documentary arena, along with his outlook on the vicissitudes of the sector.

SB: You’ve had an illustrious film career spanning more than four decades while working in roles such as director, producer, editor, sound editor, and writer—with pictures ranging from the mainstream flicks Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), Reds (1981), Casualties of War (1989), School Daze (1988) and Carlito’s Way (1993) to documentaries that have included Old Friends (2015) plus the aforementioned Getting Back to Abnormal and Somewhere to Be. What would you say are the main differences in terms of creative control with regard to working on feature films versus documentaries, and do you have a preference for either medium?

PO: My work on feature films was mostly as a sound editor. I was an associate sound editor on Warren Beatty’s Reds, and my last sound editing job was on Brian De Palma’s Carlito’s Way. During those years, sound editors in NYC almost always got to screen reels with the director to hear his or her thoughts. We suggested sound effects and ambiances that could make scenes play better, and we got an opportunity to contribute to the director’s vision and be recognized for that contribution. We felt like we were a part of a creative team. But for some reason, as sound editing moved from Moviolas and film reels to Pro Tools on computers, sound-editing work on features became more fragmented and more isolated from the director and the final product. We became less likely to meet with directors and less likely to feel that we had any creative input.

Just about everyone working in film wants a chance to express themselves, and as the years went by I realized that if I wanted more control I had to make a change. Editing documentaries, especially unscripted projects where editors work at telling a story with whatever was shot, provided a much more challenging and satisfying opportunity. I’ve edited over 20 documentaries in the past 25 years, and I eventually started producing and directing them.

How did you get into the movie business, and what predicated your move to a primarily documentary-focused output?

How did you get into the movie business, and what predicated your move to a primarily documentary-focused output?

My first paying film job was as an apprentice editor at a TV commercial editing house called Harvey’s Place. We cut commercials for Cadillac and Chevrolet, Roach Motel, Greyhound buses and more. I worked there for five years doing assistant editor work, recording voiceovers, sound mixing, and doing whatever else was needed. I left commercials in 1979 to work on features, worked on more than 15 as a sound editor, and then started cutting documentaries in the late 1980s. A lot of serendipity and the need to pay the rent shaped many turns in my career path, but there was always a desire to work on projects that gave me a chance to say something that I wanted to say in a graceful and powerful way. After features, I edited, co-produced and directed documentaries at The Center for New American Media with my partners Andy Kolker and Louis Alvarez for over 15 years, and eventually I went off on my own and made Old Friends and Somewhere to Be.

Somewhere to Be, about an unusual senior center, has received positive reviews and now has film-festival credentials. Can you tell us a little about how this documentary came about and why you were drawn to the subject matter?

What I hope to capture when making a documentary is not that different from what I hope to see in a dramatic film. I’m interested in putting something on the screen that people can empathize with, something that rings true, characters that reveal something personal about themselves. A friend told me that I had to come and take a look at this senior center that he had been going to for many years. In the fall of 2016, I had lunch with him at the center because he was confident that once I met some of the people who use it, the staff who keep it going, and the volunteers who work there every day, I would want to try and capture it all on film. He was right, and I shot there for the next six months. Somewhere to Be was finished a couple of years later.

What are the primary risks of being a documentarian, and what are the main rewards? How do you get “seen” in such a competitive landscape?

The first and most intimidating risk is that you often have to commit to a project without really knowing how it’s going to work out. You start shooting, and before you know it you’re in for the long haul. Whatever direction the story goes, you keep following, you keep shooting. Sometimes you end up close to somewhere you imagined and sometimes some place very different. Sometimes toward something more interesting and sometimes to nowhere at all. If you got less than you hoped for while shooting, you have to work much harder to produce a decent film.

Once you’ve finished shooting and editing, there is almost no possibility of any financial rewards. If you were able to get a grant from a private foundation or a government agency, you probably were able to pay yourself a salary for some of the many hours you put into the project, but there’s almost no chance of making any money from distribution. Every year there are over 2,000 feature-length documentaries made, and you have to compete with all of them at film festivals, broadcast and cable networks, and online streaming providers. It’s ridiculously difficult, but for some reason thousands of people work on documentaries every year and are grateful if they can get a chance to make one more film. I’m one of those people, and I’m very thankful for every new documentary project of mine that gets off the ground.

Although some of your films, such as Getting Back to Abnormal, which scrutinizes the attitudes and behaviors in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, have a political context, other more recent ones, such as Old Friends and Somewhere to Be, take a more personal tack … specifically with respect to aging. Do you have a sense of what is more important in the long run as a theme for cinematic posterity, and what you’d like to be remembered for?

Although some of your films, such as Getting Back to Abnormal, which scrutinizes the attitudes and behaviors in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, have a political context, other more recent ones, such as Old Friends and Somewhere to Be, take a more personal tack … specifically with respect to aging. Do you have a sense of what is more important in the long run as a theme for cinematic posterity, and what you’d like to be remembered for?

I’m most interested in making films about everyday life that somehow, hopefully, end up being somewhat artful. Gracefulness is also important to me, and when I finally started making films on my own with no co-producers or crew, gracefulness and artfulness guided much of my decision-making. My first two solo films were about friendship and kindness because those are common aspects of everyday life that we all share and parts of familiar situations and emotions that we can all empathize with. I honestly have no real expectation of making any contribution to cinematic posterity, but if someone does remember my work, I hope they remember the empathic, artful rhythms of my films.

On many of your films, you serve in variety of roles concurrently, from director to producer to editor. This must be a lot of work! How do you juggle the deadlines, budgets and tasks to generate the films you create?

I literally work alone, and working alone can be overwhelming, but it also makes many aspects of filmmaking simpler. Here are some of the advantages:

- Because I work alone, I don’t have any meetings and I don’t have to persuade anyone of anything.

- I don’t have to raise money because I have only one employee, myself, and I don’t get paid.

- I have no budgets to juggle because there’s no budget.

- I have no deadlines except ones that are self-imposed.

- I worked collaboratively for 40 years, and working solo is what suits me best at age 69.

Your wife, noted poet Esther Cohen, and your sister Betty make appearances in Old Friends, while your mother makes a cameo in a documentary you edited called Moms (1999). What was it like to work with family members on these projects … and was the aggravation minimized?

My mother was near the end of her life when she appeared in Moms, a documentary about the joys and sorrows of motherhood. Her cameo was just a shot of me gently kissing her on the cheek; she had suffered a stroke and really wasn’t able to speak anymore. In her prime, my mother was more than capable of aggravating me, but as she was fading away, she was just happy to see me, and it was very moving for me to spend a little time with her.

I never set out to make an autobiographical film, but ending up telling a personal story happens to documentary makers from time to time. In my case, the result was Old Friends. Working with my wife, Esther, and my sister, Betty, and 14 friends of mine was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. All concerned wanted the documentary to be a success, so they all tried to tell me something special when I turned on the camera. The intimacy and honesty were very powerful. Even the way that Esther and I love each other magically comes across in the film. Old Friends was one of the most straightforward, naturally falling-into-place filmmaking experiences I have ever had, and that makes a difference in how the film reaches out to the audience.

What is your next project, and what would you like to work on in the future? Are there significant innovations in the world of documentary filmmaking that would transform the genre, and if so, how? And what kinds of changes have occurred in the world of documentary festivals over the last 40 years that would affect the arena?

In the near future, I hope festivals will more often recognize documentaries that reveal some of the same aspects of the human condition that dramatic films depict. If the powers that be at festivals begin to reward documentaries based on criteria that are less journalistic and more similar to how they might judge a dramatic film, that might encourage people to try and make more graceful films that capture the complexities of everyday life. Hopefully, my future films will be among the documentaries that try and make the everyday more visible.

Comments

One response to “Interviewing Peter Odabashian: Drama in the Documentary Art Form”

Great interview, Simon.