Anyone care to explain why music from Richard Wagner’s seminal opera Tristan und Isolde, which tells the story of the doomed love between Arthurian Knight of the Round Table Sir Tristan and the already married queen Iseult, is used to accent scenes featuring the fellow warrior Lancelot and his lord’s wife Guinevere in John Boorman’s 1981 fantasy Excalibur?

Anyone care to explain why music from Richard Wagner’s seminal opera Tristan und Isolde, which tells the story of the doomed love between Arthurian Knight of the Round Table Sir Tristan and the already married queen Iseult, is used to accent scenes featuring the fellow warrior Lancelot and his lord’s wife Guinevere in John Boorman’s 1981 fantasy Excalibur?

Yeah, it sounds good; that’s a given. But does it fit? The context sure as hell doesn’t. They’re two different stories.

I know, I know: I already wrote about this—specifically, in a recent article for CURNBLOG discussing the use of Pietro Mascagni’s “Intermezzo” from his opera Cavalleria Rusticana in the 1980 film Raging Bull and the 1990 picture The Godfather Part III. In that post, I wondered whether the effects of the piece were diluted through its use in two different, though incredibly effective, cinematic settings. So, yes, I’ve covered this ground before.

But not completely.

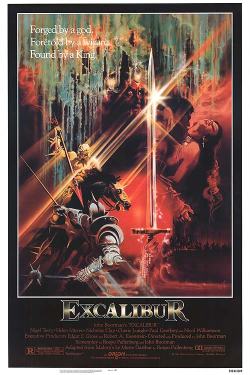

See, Excalibur poses some other issues. The film is a lot of fun. Has some incoherent spots, and of course, it’s quite abridged, yet it still works as a telling of the Malory-informed King Arthur legend. Problem is, though, that much of the music in the flick comprises classical compositions from the last couple of centuries. And those aren’t just any compositions, mind you—they’re some of the most indelible works in the canon. Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana.

Well, some might say, so what? They support the action pretty darn well in the film.

Yes, but that’s not the point. The music incorporated into these sequences had, with few exceptions, wholly different contexts from the proceedings onscreen. Tristan and Isolde versus Lancelot and Guinevere is just one example. Another is the Teutonic hero Siegfried’s death and funeral march from Götterdämmerung sounding so triumphantly in the background while a vicious battle is being fought by Uther Pendragon, Arthur’s father, against his enemies. That same theme plays at the end of Excalibur, when Sir Percival throws the magical sword Excalibur away, to be caught by the Lady of the Lake, as well as when the dying Arthur is carried off on an enchanted ship.

Götterdämmerung, however, is about the end of Wotan and all the other gods of the ancient Germanic pantheon. They pretty much all die at the end of the opera, and the legendary protagonist Siegfried’s demise basically serves as a premonition of things to come. Valhalla is destroyed. That the music surrounding Siegfried’s funeral is so glorious makes for a brilliant counterpoint to the activities in the latter parts of the opera. It’s no wonder Boorman liked it enough to use it.

Still, it doesn’t make sense. The legend of King Arthur is infused with the spirit of Christianity, in contrast to the mythological contexts of Wotan (aka the Norse Odin), Siegfried, et al. The pagan elements of Arthurian legend are alluded to by Merlin (played bizarrely and somewhat amusingly by Nicol Williamson) at one point in Excalibur, but for the most part, it adheres to its monotheistic subtext. And the story of Siegfried is just not the same story as the one of the once and future king … or Uther Pendragon, his father, for that matter. It’s just not.

Neither is Orff’s Carmina Burana, a 1930s cantata that uses a variety of love poems conveyed in Latin, among other content, as its texts. “O Fortuna,” the pulsating, ominous starter for this song cycle, is used in Excalibur to thrilling effect, as Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table ride to battle against archenemy Mordred while the flowers of spring fall around them. It’s extraordinary filmmaking. Trouble is, it’s out of context. If you read the lyrics, they’re kind of mournful: railing against fortune, that sort of thing. Not the kind of thing you’d expect to be a rallying cry for the most famous legendary king of Britain.

Neither is Orff’s Carmina Burana, a 1930s cantata that uses a variety of love poems conveyed in Latin, among other content, as its texts. “O Fortuna,” the pulsating, ominous starter for this song cycle, is used in Excalibur to thrilling effect, as Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table ride to battle against archenemy Mordred while the flowers of spring fall around them. It’s extraordinary filmmaking. Trouble is, it’s out of context. If you read the lyrics, they’re kind of mournful: railing against fortune, that sort of thing. Not the kind of thing you’d expect to be a rallying cry for the most famous legendary king of Britain.

That, in essence, is the issue. These pieces of music were selected because they sounded cool. Perhaps also because they had mythic qualities with regard to their source material. But if one examines them closely, it might be suggested that they were poor choices. The Tristan und Isolde scenes are like a joke. The themes used are among the most famous in classical music. And they’re the wrong story. Same with Siegfried’s death and funeral march at the beginning and end of Excalibur. Incorrect context, Boorman baby. Verily, it’s rollicking and all that, but upon further inspection, they don’t hold up to the meaning police. And don’t get me started on Orff. It offers just more proof that all too often, sound and fury don’t always tell the entire tale.

Then what do I want? Should all film music be devoid of any programmatic intimations? Should we stop using Verdi’s Requiem in commercials and film trailers? Or the famous “Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen” aria sung by the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute in, well … anything other than its original source? That could even extend to rock music. I mean, imagine Martin Scorsese not being able to use The Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” in one of his movies because the actions occurring on celluloid don’t have anything to do with the lyrics. What a world that would be.

Hey, I’m not recommending this should happen. Yet it does bug me more than a little when great works of music are used in ways they are not intended … especially when such usage appears to be willfully ignorant of the original scope and instead focuses, in a shallow manner, on the aural qualities. Boorman did just that in Excalibur with Wagner and Orff. In doing so, he created, in my opinion, something of an ethical mess.

He did have one redeeming moment, though: The scenes in which Sir Percival finds the Holy Grail. Yes, the gorgeous prelude from Wagner’s magnificent opera Parsifal is performed, and that’s exactly right. Why? Because Parsifal is Percival. It’s the same character, just translated to a Wagnerian setting. This is one spot where Boorman’s choices fit the bill.

A taste for fine classical music, however, doesn’t necessitate its use in irrelevant material, and I think that’s part of the dilemma with the rest of Excalibur. True, we’ve seen the effective use of Tristan und Isolde in other pictures, including, memorably, Luis Buñuel’s inimitable Un Chien Andalou (1929), where it manifests itself as kind of a snarky soundtrack to the wildly surreal and deliberately incomprehensible goings-on of the film. And, yeah: We have none other than Malcolm McDowell’s Alex warbling “Singin’ in the Rain” at inopportune moments (including during a horrific rape scene) in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). The difference is, though, that in these latter two contexts, the music is used as commentary. Both are very familiar melodies, and both are used in an off-putting, negative way that could potentially incite dialogue. Conversation.

The utilization of Wagner and Orff in Excalibur, for the most part, seems designed to laminate the occurrences onscreen rather than provide any subversive or even mildly critical insights that might bolster viewers’ opinions about these musical works and their appearances in other settings. What happens is that the melodies become obvious; they stick out. We realize it’s Tristan und Isolde they’re playing; we realize it’s Carmina Burana. It becomes all the more jarring. They don’t belong. They don’t say anything new.

They do, on the other hand, call attention to the fact that they’re misplaced. And that just doesn’t work. It. Just. Doesn’t.

I’d like advertisers to think about this whenever they consider using Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London” in a commercial … without the lyrics. Or The Who’s “Baba O’Riley.” It may make money for people, including those who lend their tunes to TV spots, trailers, series, and movies, but there may be something lost in translation. For those who recognize the original sources of these melodies, the out-of-context application may be eyebrow-raising, to say the least. This is why directors of the small and big screens need to take more care when picking out their musical accompaniments. There should be more method than madness. If there’s in excess of the latter instead of the former, we might have some kind of aural chaos ensuing. You know: dogs and cats living together. Mass hysteria. A world where folks like Bruckner more than Beethoven, Sondheim more than Bernstein.

I don’t think that will happen, but you never know in this age of taking things that are old and putting them into newer, unrelated contexts. Boorman’s Excalibur reflects this very concern. It showcases the problem with fitting round pegs into square holes when both happen to be the same color. Superficiality just won’t cut it. The shape has got to be the same, too.

Give me that, and I’ll sing the “Liebestod” from Tristan for you any day. As long as you won’t miss the high notes. Or mind me transposing the score a few octaves downward.

For, as you know, context is everything. And if I can’t sing something in the original way, it’s probably best … that I still sing it the way I want.

Because I never said all this applies to me.

Comments

4 responses to “Musical Snares, Part II: ‘Excalibur,’ Wagner and the Context of Melody”

The idea of a jarring misfit betwixt musical context and film is only a problem when the viewer both knows the original context and cares that it doesn’t fit the film. Many viewers (in my experience) don’t even know what they’re listening to when a famous piece of music shows up in a film, much less realize what it originally meant. The only meaningful measure of the success of music-film paring is does it create the appropriate emotional response in the viewer. If a viewer is aware of an original meaning to the music, and that it is contrary to the current application in the film, it could certainly pose problems for that viewer, so your point is not completely void. I haven’t seen Excalibur so I can’t say whether these issues would interfer with my perception of the film, but now I want to find out! But there is the added layer that now when I watch I will be hyperaware of the music and even less able to innocently absorb the film without prejudice. But I’ll do my best in the spirit of cinephilia.

Your points may be valid, but average movie goers aren’t interested in dissecting the innards of a movie. They just want to be entertained…

For years I have been droning on about non-connected music in films.

For a start, soundtracks should be separated into collations and scores.

Mothersbaugh does collations; Morricone does scores. The two are different beasties.

But, say, A Quick One by The Who is less about Bill Murray walking and more about Mark M. showcasing his cool taste in tunes. The scores of Ennio M. are much more about what is happening onscreen.

Needless to say, I find Scorsese and his collations less appealing than Jerry Goldsmith or Lalo Shifrin’s score.

In fact, cynical me thinks collations all about the filmmaker showing off his taste, flogging merch, or both.

When I went to see ‘Excalibur’ in a cinema in London on release, I had never heard of ‘Carmina Burana’. I thought it was amazing in the film, out of context or not. Soon after, I tracked down a version of Orff’s work on vinyl, and played it constantly, reading the words on the fold-out cover.

So if nothing else, the use of that music on the soundtrack broadened my own musical horizons.

Best wishes, Pete.