Allow me to ask you a few potentially offensive cinema-focused questions.

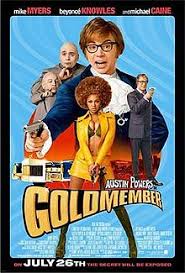

Allow me to ask you a few potentially offensive cinema-focused questions.Did you giggle at the line in Woody Allen’s 1975 comedy Love and Death in which Diane Keaton’s character Sonja says of her one true love, “Boris is trying to commit suicide—last week he contemplated inhaling next to an Armenian”? How about chuckle at the scene in the 1990 film Ghost where Whoopi Goldberg’s psychic Oda Mae Brown warns grieving widow Molly Jensen that Willie Lopez, the brutal hit man who killed her husband, is out to get her and “he’s Puerto Rican”? Or guffaw when the silly-yet-oftentimes-crafted-to-seem-relatable Dr. Evil in Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002) complains to the supposedly Netherlands-originated villain Goldmember that he doesn’t “speak freaky-deaky Dutch” or calls the guy a “crazy Dutch bastard”?

All of these quotes have a couple of things in common: 1) They are played for laughs; and 2) they aim to insult specific ethnicities for no apparent reason. That’s right—I did say “for no apparent reason.” But there may be an actual motive behind their utterances that, while not being crystal-clear, forms the basis of a particularly insidious type of entertainment gathering steam in the movie universe.

And such a rationale is assumedly all about lampooning individuals of selected nationalities that are, in the filmmakers’ estimation, unlikely either to comprise a large part of the pictures’ audiences or to voice significant complaints about such celluloid treatment … or both.

At least, that’s what I’m surmising here. Yet it’s not an isolated phenomenon. In an earlier piece for CURNBLOG, I wrote about what appears to be bigotry against and criticism of the Japanese in the flicks Silence (2016) and Get Out (2017). Those movies problematically depict the aforementioned ethnicity in negative ways, though the manners in which they convey such messages differ. Silence appears to lambaste Buddhist and/or Shintoist Japanese in its suggestion that most, if not all, such populations exhibited apathy or callousness toward those of their own heritage who were being persecuted for converting to Christianity during the Tokugawa era, while Get Out populates its gaggle of otherwise blandly homogeneous Caucasian malfeasants out to possess African-Americans’ bodies with a lone fellow sporting a Japanese name and played by a performer possessing that ancestry.

These concerns stick out and call attention to what may or may not be a deliberate attempt to paint one group with a broad, offensive brush. Movies are not like real life. Whereas we may have baddies doing bad things that are of one race or another off the silver screen, just as we do have good guys of those same ethnic groups acting the opposite fashion, the cinema, because of its dependence on editing, photography, writing, directing, and acting, among other elements, is not so egalitarian. There’s no way to ignore character identity in Technicolor. Meanies like James Bond nemesis Dr. No? Supposed to be part-Chinese. Jerks such as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)? Japanese, once again … and stereotypical up the wazoo. Insensitive twits such as Dr. Silberman in The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2 (1991)? Clearly the standard, clichéd Jewish psychologist, though this is inferred, as it was not specified in the picture. In the last cases, it might not be supposed that Jewish film-lovers wouldn’t flock and haven’t flocked to see former California Governator Arnold Schwarzenegger cause mayhem galore as a nearly indestructible cyborg in a highly popular sci-fi franchise. But do you think the makers of Dr. No (1962) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s counted on audiences of Chinese and Japanese descent, respectively, to the theaters for an experience that basically denigrates folks who share their cultural heritage? There are no “good” Chinese characters to speak of in the film of Dr. No; likewise, there are no positive Japanese portrayals in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Still, who cares, right? These are classic films. Quality cinema trumps any suggestion of bias.

The three offensive depictions I cite in the first paragraph of this essay point to this problem in especially disturbing ways. Love and Death’s noxious reference to the purported bad smell of Armenians is meant to amuse yet is so completely derogatory that it begs the question of where did such a repugnant stereotype come from? It certainly has little, if any, precedent in American cinema; therefore, it appears to be clear that Allen, who wrote the script to the film, aimed his sights at a population no one would conceivably think had such a reputation or would run to see his niche-y, insular pictures … hence the comedy. Making fun of folks we don’t know about or have anything to do with is humorous, see? That’s the essence of comedy.

In the case of Ghost, the aforementioned line is somewhat more telling. Oda Mae supposes the villain is Puerto Rican because of his Hispanic name. Why Puerto Rican? Well, perhaps she’s seen West Side Story (1961), which, though laced with brief attempts to be balanced in its albeit stylized conveyance of gang life in New York City, still gives the role of the Capulets in this adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to the former residents of that “ugly island/Island of tropic diseases” (in the words of the original version of the song “America” from the Broadway show). Or maybe she subscribes to the asinine, unfounded misconception that all Puerto Ricans are lowlifes, lazy or criminals … vicious, xenophobic stereotypes that came to the fore in the mainland United States following the move of thousands of individuals from the territory to the country in the 20th century. Notice that Oda Mae doesn’t cite any other group with a culture deriving in part from Spain. She says “Puerto Rican.” And although Lopez’s ethnicity isn’t mentioned elsewhere in the film, she has to surmise that. Because it’s funny. We can laugh at the fact that she jumps to that conclusion.

In the case of Ghost, the aforementioned line is somewhat more telling. Oda Mae supposes the villain is Puerto Rican because of his Hispanic name. Why Puerto Rican? Well, perhaps she’s seen West Side Story (1961), which, though laced with brief attempts to be balanced in its albeit stylized conveyance of gang life in New York City, still gives the role of the Capulets in this adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to the former residents of that “ugly island/Island of tropic diseases” (in the words of the original version of the song “America” from the Broadway show). Or maybe she subscribes to the asinine, unfounded misconception that all Puerto Ricans are lowlifes, lazy or criminals … vicious, xenophobic stereotypes that came to the fore in the mainland United States following the move of thousands of individuals from the territory to the country in the 20th century. Notice that Oda Mae doesn’t cite any other group with a culture deriving in part from Spain. She says “Puerto Rican.” And although Lopez’s ethnicity isn’t mentioned elsewhere in the film, she has to surmise that. Because it’s funny. We can laugh at the fact that she jumps to that conclusion.

She’s a heroine in the film, by the way.

The case of Goldmember is a bizarre, though no less insulting one, owing to its choice of racial ridiculing. The weird crook Goldmember announces he’s Dutch, eats large portions of his own skin peelings, speaks with a ridiculous accent and references facets of Netherlandish cuisine, including pancakes. Oh, and he’s an idiot who is frequently chastised by his comrade-in-wrongdoing Dr. Evil, himself an absurd character yet somehow shown as more realistic than his imbecilic associate. Comedian Mike Myers, who cowrote the script, is no stranger to racial caricature; one of the other crooks in the Austin Powers series is a morbidly obese dude named “Fat Bastard’ who speaks with an exaggerated Scottish accent and sometimes even wears clothing that hearkens back to the styles of the land. Myers, who also went into full Scottish impersonation mode in So I Married an Axe Murderer (1993) with characterizations of the ethnicity among members of his cinematic family that bordered on the inane, reportedly has Scottish heritage and perhaps may be seen as broadcasting an affectionate nod to his culture in affecting these impersonations. The Dutch thing, however, is totally out of the blue, and Goldmember, as a film, can’t seem to decide whether it wants to stick with the idea of satirizing the denizens of the Low Countries or scold those who adhere to such bigotry. (For example, Austin Powers’ father Nigel, who amazingly looks for all the world like actor Michael Caine, says at one point: “There are only two things I can’t stand in this world: People who are intolerant of other people’s cultures, and the Dutch.”)

Then what’s it all about, Alfie? Does Myers think the Netherlands is too small a nation to be bothered by verbal barbs directed at its citizens? Or maybe that there aren’t enough Americans of Dutch stock who would go to see (and now, perhaps, rent on demand) Goldmember? Given New York City’s former status as a Dutch colony, I’d say this type of thinking wouldn’t make any sense in that cinema-loving town specifically, and it shouldn’t fly elsewhere, either.

The thing about comedy is that the legitimacy of ethnic portrayals depends on the context, as well as the content. Mel Brooks’ and Madeline Kahn’s over-the-top gag as an elderly Jewish couple trying to get through airport security in High Anxiety (1977) is hysterical but not, at least to me, offensive, given the Jewish roots of both of the performers and the fact that it’s totally off-the-wall. Then you have African-American actor Eddie Murphy in makeup playing an alter kocker Yiddishe man in Coming to America (1988) that’s a scream and also, to me, not offensive, as it’s something of a positive portrayal, isn’t conveyed as an object of ridicule and has a lot of funny lines. Plus, as a Jew, I find Murphy’s accent just brilliant; sure, it’s exaggerated, but it also brings back memories of my Hebraic journeys past, to the Lower East Side in Manhattan where such inflections were, once upon a time, prevalent, and where I spent a lot of the time as a child. Eddie does it right.

Love and Death, Ghost and Goldmember don’t.

Many claim that comedy is subjective. Many argue that you can’t take the offensive out of humor because there would be nothing left. I say stuff and nonsense. There’s a difference between being fond and being mean-spirited, and though the world of laughter often straddles those lines, there’s no reason to stomp on the nationalities of those you don’t think would give a damn about being stomped on, presumably because of the limited access or appeal of such endeavors to these groups and/or their capacity for protest. Ethnic humor can be funny, even when not delivered by those of the same ethnicities … as long as it’s done correctly. And singling out any specific community for unmitigated, unwarranted skewering is just plain wrong.

Many claim that comedy is subjective. Many argue that you can’t take the offensive out of humor because there would be nothing left. I say stuff and nonsense. There’s a difference between being fond and being mean-spirited, and though the world of laughter often straddles those lines, there’s no reason to stomp on the nationalities of those you don’t think would give a damn about being stomped on, presumably because of the limited access or appeal of such endeavors to these groups and/or their capacity for protest. Ethnic humor can be funny, even when not delivered by those of the same ethnicities … as long as it’s done correctly. And singling out any specific community for unmitigated, unwarranted skewering is just plain wrong.

Perhaps the wisest words in this regard might come from an unexpected source: Groucho Marx in the movie Monkey Business (1931), who puts down a belligerent costume party attendee dressed as a stereotypical American Indian—complete with feathered headdress—with the line: “Well, if you don’t like our country, why don’t you go back where you came from?”

It’s clear whom he’s insulting there, and despite Marx’s beyond-disrespectful whooping after this interaction, the line that precedes it may say quite a bit about what it means to mock people who deserve to be mocked … and those who don’t. My feeling is that more filmmakers would do well to take a page out of his book in this sense, which would lead to fewer undeserved insults and more deserved hilarity.

Any other approach would just make a farce of comedy. And in this cinemaniac’s opinion, there’s nothing whatsoever funny about that.

Comments

5 responses to “Laughter in the Pain: When Movie Humor Crosses the Bigotry Border”

Mr Butler should turn his writings into a monograph called “My offence is your offence: a dictation of textual errors in world history in thirty-seven volumes”.

Other than maintaining a state of being perpetually offended, is there a point to pointing out these misinterpreted scenes? Maybe, just maybe, there’s nothing wrong with those of us who laugh at these scenes…

I have never seen any of the three you discussed, but I have seen the problem and actually gasped at hearing it in other films.

I agree that Mel Brooks does it right. It’s done so well in Blazing Saddles, too.

Terrific article. I enjoyed it a lot.

I didn’t laugh at those lines in ‘Love and Death’, or ‘Ghost’. And I didn’t find the ‘Dutch’ references remotely amusing. But I confess that I did laugh at ‘Fat Bastard’ being Scottish. That could be because I come from England, where we have a long history of mutual insults between us and Scotland. In my case, it was playing more to tradition, than stereotyping.

An interesting article, Simon, and it made me think about just how many other examples pass almost unnoticed in films.

Best wishes, Pete.

Interesting article, Simon!

I have to admit, I don’t see the references in Love and Death and Goldmember in quite the same way.

In ‘Love and Death’, I interpret the moment you mention as a parody of prejudice – a recognisable moment for Americans, placed in an alternate situation that highlights the absurdity of the whole thing.

In Goldmember, the joke seems to be that the stereotype is so broad as to be entirely unrecognisable. It’s meaninglessness is almost the joke. It reminds of the ‘Australia’ episode of The Simpsons, which has become quite a favourite in Oz not because of its incisiveness, but because it’s broad misintepretation of Australia is so off the mark it’s almost genius. (I’m in no way suggesting Goldmember is brilliant – it’s a mess)